Bankes Reunion, 18 June 2011: John Bankes Talk Notes

John Bankes, Citizen & Haberdasher of London, c1650-1719

Index & Links to Sections

1. Introduction

2. John Bankes’ Birth

3. John Bankes’ First Marriage

4. John Bankes’ Second Marriage

5. John Bankes’Death

6. John Bankes’Occupation / Business

7. John Bankes’ Properties

8. John Bankes’Business Mortgages

9. John Bankes and the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers

10. John Bankes’Religion

11. John Bankes’ Residential Properties

12. John Bankes’Unresolved Query 1 – Birth

13. John Bankes’Unresolved Query 2 – First Marriage

14. John Bankes Summing Up – An Enigma

As this day is billed as a reunion of John Bankes’ Descendants it seems appropriate for me to say a few words about this gentlemen, who had such an influence on our various families. Indeed, even in this room there is at least one person who has ‘Bankes’ in his name.

I and a number of fellow researchers have been researching this man and his pedigree for over twenty years now, and during that time we’ve learned a lot about John Bankes and the Bankes Pedigree. Of course, none of us are descended from Bankes. According to his Will he had had eight children and they all died before him.

Anyway, in this talk my aim is to give you some basic information about this man –

Information about who he was – his birth, marriages etc

- What he did – his occupation, his religion etc

- The places where he lived

- The problems thrown up by the question of When he lived.

So let’s start with the question – Who was John Bankes?

Back to top

2. John Bankes’ Birth

We have no actual evidence of his birth, and therefore the date that we have calculated is inferred from a couple of sources:

- 10 March 1673 – Freedom Record Haberdashers’ Company – indicates over 21 at that date.

- 09 May 1715 – Marriage Licence Allegation re second marriage states Aged 60

I think the most reliable of these is the record of his being granted the Freedom of the City of London in 1673. After all, it would not be unusual for a person to be ‘economical with the truth’ in disclosing his age in his later years.

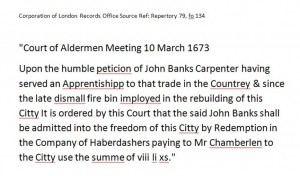

John Bankes, Citizen & Haberdasher of London - Freedom Record, 1673

I haven’t got a copy of this document, I’m afraid, so we have to make do with the above transcription. It is a few years since we looked at the document, and in those days you couldn’t use a digital camera to record such items. Also, photocopying these old documents could also be problematic. At the time when I saw this record it was held at the Corporation of London Records Office, but it now resides at London Metropolitan Archives.

So what does this source tell us about Bankes’ date of birth?

Well, nothing directly. However, we can see that our man had served an apprenticeship as a Carpenter. Apprenticeships almost always started when the apprentice was 14 years old, and ran for seven years. Thus, Bankes must have been at least 21 when he obtained his Freedom, meaning that he was very likely born in about 1652.

The way the document reads suggests that he had been working in the building trade in the City of London since he completed his apprenticeship, so he may have been a bit older than 21. Let’s assume that he may have been about 23 ish. Hence our estimate that Bankes was very likely born between 1650 and 1652.

Actually, we do have direct evidence of his age, because when he swore his marriage licence for his second marriage he said that he was 60 years old. That was in 1715, so would make him born about 1655. However, if this were true Bankes would have only been 18 in 1673, and that cannot be so, because you had to be 21 to get your Freedom. Thus, it looks as though he understated his age.

From this we learn that John Bankes probably suffered from a degree of vanity! I wonder what he had told his bride about his age!

3. John Bankes’ First Marriage

Now we turn to John Bankes’ first marriage.

His Will names his first wife as Elizabeth Atherton, and also names some of her relations – Humphrey Atherton, Augustine Atherton, Daniel Atherton and so on.

We don’t know when or where this marriage took place, but they must have been married for a few years if they produced eight children!

According to the Poll Tax records of 1692 Bankes was living at Paul’s Wharf, London, and included in his household were a wife and one child. Unfortunately, wives and children were not important in the eyes of the tax man, so they were not named in this source. We can, however, guess that the wife was almost certainly Elizabeth, which would suggest that this marriage probably took place by about 1690.

It is likely that Bankes was at least 21 when he was married, in which case he probably got married after about 1672, and as we are pretty sure that from that date onwards he was living in London, we assume that the marriage probably took place in the capital.

Jane Stacey is with us today, and some years ago she did some research in the Oxfordshire parish registers, trying to trace the Athertons. I’ll explain why Marsh Baldon a bit later.

Anyway, Jane came up with baptism date of 1640 for a lady who could well have been John’s first wife, and that really gives us our working hypothesis for this date.

What we do know is that by 1715 Elizabeth Atherton Bankes had died. Either that or John Bankes was a bigamist, and I doubt that!

4. John Bankes’ Second Marriage

Because in 1715 our John married for the second time, at Holy Trinity, Knightsbridge in London.

This time we do know quite a lot about the event and John’s bride.

I’ve already mentioned the marriage licence allegation relating to this wedding. This affidavit was sworn on 9th May 1715 by John Bankes, a widower of St Bennett’s Pauls Wharf in London, a merchant, aged 60 years. His bride to be was a certain Elizabeth Trevers, a widow of St Olave Southwark, aged 45. At the bottom the document bears our man’s signature.

I found this document some years ago in the records of the Vicar General’s Office in the library of the Society of Genealogists, and you can’t imagine how excited I was!

Three days after Bankes swore this affidavit – on 12th may 1715 – the marriage took place. Unfortunately the records of Holy Trinity Chapel, Knightsbridge no longer exist, but luckilyly there is a transcription of them in the SOG Library, and that is where I found the record of the marriage.

So who was Elizabeth Trevers Bankes?

Well, it came to light during our research that she was the mother of Elizabeth Russell, who married Bankes’ nephew – Robert Mitchell, Skinner. Knowing that she came from the Southwark area I searched the London parish registers and tracked her down in Bermondsey as Elizabeth Russell. We’ve traced a number of her children and their marriages. In fact we do have a fair bit of information about these people.

Thus far I’ve covered hatches and matches, so we’d better cover the despatches as well. John Bankes died on 23rd March 1719. Under the old Julian calendar , under which the year changed on 25th March, that date would have been in 1719, but under the Gregorian Calendar where the new year starts on 1st January it would have been in 1720. Whatever, Bankes’ Will was proved in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury on 26th April 1720, the executors being John Hales, a Gentleman, and John Cartlitch, a Goldsmith, both of London. They were business associates of Bankes, and also, apparently, friends. If you want to look at the will you can get a copy online on the National Archives website for £3.50.

For copyright reasons we cannot show on this website the copy of Bankes’ will that was displayed as a slide in this talk. I found it in a bundle of Court of Chancery documents that are held at Kew. I couldn’t look at all of it as a number of pages have been fixed together, but I could see that it bears a seal, and would not be surprised if it was used in the granting of probate. Something to look at again when I can, I think.

The will stipulated that Bankes be buried in the Bishop of Winchester’s burial ground, which was a non-conformist burial ground in Southwark, commonly known as Deadman’s Place. No records survive for this burial ground, but it seems reasonable to assume that the deceased’s wishes were carried out. Bankes’ will says that his first wife had been buried there, as well as a daughter, who he named as Esther.

As a matter of interest this burial ground was cleared some time later, and Barclay’s Brewery was built on the site. Apparently this was one of the biggest breweries in the world, and in 1861 a Bankes descendant – John Hunt, son of Dr Thomas Hunt, worked there as a clerk.

So much for Who?

Now we move on to What?

6. John Bankes’ Occupation / Business

What did John Bankes do for a living?

The above slide lists a few of the descriptions of Bankes’ occupation that we have noted over the years.

The first thing to note is that the fact that a person was a freeman of a particular livery company does not mean that he followed that trade, and that is still true today, so the fact that Bankes was a Citizen & Haberdasher is not meaningful in this context. When my mother kicked off our research she was told by the archivist at the haberdashers company that our man was a mercer, trading in the eastern Mediterranean, but as our research progressed we realised that this was not so.

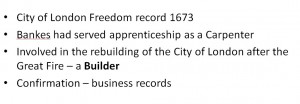

Some evidence of the business activities of John Bankes (c1650-1719)

Over the course of our research we have found lots of evidence about JB’s occupation. He was involved in the building trade in London, importing timber from Scandinavia and, we think, from the Baltic. He used to take out leases on pieces of land, build on them, then rent the properties out to tenants. Presumably he also sold some of the properties as well.

We can see from the documents that survive that he was largely building residential properties, but he also built business properties, as can be seen from the fact that in 1703 he built Harcourt Buildings in the Temple, London. This building seems to have housed a number of firms of lawyers.

Some documents evidencing the business activities of John Bankes (c1650-1719)

The above slide lists some of the evidence of Bankes’ occupation that we have come across in researching his business accounts. We have also found some original bills for goods and services supplied to Bankes in the process of his activities building properties in London and Middlesex. We have found these in the Court of Chancery records, and the National Archives source reference for them is C105/21. You can see exmples of these sources in the John Bankes section of the Geoff’s Genealogy website.

The items shown in the talk were:

A record of purchases made by Bankes for his estate in Mary Gold Alley, which was just off the Strand in London. This showed that Bankes had bought some sand, lime and bricks.

A bill to Bankes for work done by bricklayers at the same location. This evidences the supply of bricks and other materials, plus labour. It seems that 4.5 days labour cost £1 2s and 6d. About 4s 6d per day, or, in modern money, 23 pence. It doesn’t seem much now, but it was a fair old sum in 1715.

As a matter of interest we have seen rental agreements for the Mary Gold Alley estate.

A page from an accounts book that Bankes left us. In this source you can see his debts at 25 December 1697 on the left, and the amounts owing to him on the right hand side. In the first two lines on the right hand side you can see the value of Bankes’ stock of bricks and lime at his yards – Paul’s Wharf and Nine Elms.

Another similar page, dated 24th December 1698. Among the creditors named by Bankes was a certain Mr Jacobson. We’ve no way of knowing whether he was a member of the Jacobson clan that features on the Bankes Pedigree in the eighteenth – nineteenth centuries.

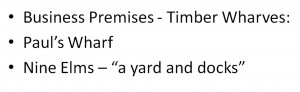

I’ve already mentioned this, but the above slide is just to list for you the locations of Bankes’ two timber yards and docks. Paul’s Wharf, which was near Blackfriars Bridge and St Pauls, and Nine Elms, which is now the home of Covent Garden market.

At this point Geoff displayed a modern map – courtesy of Google – showing roughly where Bankes’ two known yards were, and continued: As I’m sure you know, in Bankes’ time the Thames was a major London thoroughfare, and we can use our imagination to visualise all the ships that would have been on the river. For sure, Bankes must have travelled between these two workplaces by boat at least some of the time, as it was probably the quickest way to make the journey. Also, presumably the merchant vessels that carried his goods must have been plying between the two riverside wharves.

Geoff also mentioned a superb map of the St Paul’s Wharf area of London that can be seen on the Guildhall Library’s Collage website, dated 1720. It is by John Strype, and a real work of art, clearly showing the location of St Paul’s Wharf, where Bankes had a yard and dock. It is well worth a look if you get a chance. It also contains an illustration of the church of St Benet, Paul’s Wharf.

So, to sum up what we know of the business operation of John Bankes, we can say

- He was a Timber importer, and property developer.

- Typically he leased the land he built on – we know that the land on which he built his Westminster estate was leased from the Crown, for instance.

- Basically, he built properties and then rented them out to tenants.

From the records that Bankes left behind we have been able to identify a number of properties that he owned at various times:

- From his will we learn that he had a large estate in Poultney Street, Windmill Street and Princes Street in the parish of St James, Westminster. This estate originally included 72 houses in Westminster, and the income from it financed the Bankes Trust.

- From his will we also learn that of an estate that he owned in the parish of St Mary Matfellon, in Whitechapel. This consisted of thirteen leases, and he left them to members of the Rand family – the forebears of all Bankes’ descendants. As a matter of interest, this estate was in George Yard, which was later to be the scene of one of Jack the Ripper’s crimes.

- Again, from John Bankes’ will we learn that he had four properties in Great Queen Street, in the parish of St Giles in the Fields. These he left to his widow.

- We have a copy of a document dated December 1698 which lists the rents due to John Bankes on his estate at Rosemary Lane, which was near the Mint and Tower of London.

- I mentioned Harcourt Buildings earlier – these were legal chambers in the Temple area of London, built by John Bankes in 1703

- Mary Gold Alley, which was just off the Strand, features in Bankes’ records around 1715, but is not mentioned in his will.

- Goodmans Fields is in East London – Tower Hamlets. Bankes records properties there in his accounts for 1697.

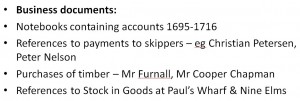

Rental agreements re the properties belonging to John Bankes

The above slide lists some more of the items of evidence we have of John Bankes’ activities as a property developer and landlord:

- We have some of his rental agreements, some of which bear the signatures of Bankes and his tenants

- Some of these agreements include a description of the property

- We have some lists of Bankes’ tenants and the amount of rent they paid

- We also have one or two drawn maps of estates under construction

At this point Geoff displayed a couple of these documents. Firstly a list Bankes’ tenants at Rosemary Lane in 1706 and then a handwritten rental agreement dated 1717 between Bankes and one of his tenants at Mary Gold Court – Peter Abell, a tailor. This image can be seen by following this link to the Geoff’s Genealogy website. On this document you can see the signatures of Peter Abell and John Bankes, and a witness – Nathan Crow. Nathan was a servant to Bankes, and we are impressed that he was able to sign his name. He must have been reasonably well educated to be able to do that.

8. John Bankes’ Business Mortgages

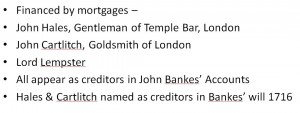

Now to the question of how Bankes financed his operations.

It is evident from his accounts that Bankes raised mortgages from three business associates, who are listed on the above slide. At the time of his death Hales & Cartlitch, both of whom were long standing business associates as well as being friends, were owed money on loans to Bankes that were then outstanding to them. As I mentioned earlier, they were both executors of Bankes’ will.

Bankes’ accounts of 1708 show Lord Lempster and John Hales featuring as creditors in that year.

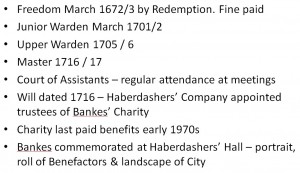

9. John Bankes and the Worshipful Company of Haberdashers

So what of John Bankes’ life as a member of the Haberdashers’ Company?

John Bankes' Career in the Haberdashers Company of London

The above slide gives you a very brief chronology of his role in the Company, but beyond these bare facts there is much more to learn. He served on the Court of Assistants – the ruling body of the company – from about 1701 right up to his death, being a Junior Warden, an Upper Warden, and finally Master. In his will he appointed the officials of the Company as the trustees of the Bankes Charity, which many of our forebears benefited from, and which ran until the early 1970s.

In his will he also said that after his widow’s death he wanted his portrait to hang in Haberdashers’ Hall in perpetuity, and it can still be seen there today. Our guess is that the portrait was probably painted around 1717, when Bankes was the Master of the company. Some years ago Geoff asked the experts at the National Portrait Gallery in London if they could identify a likely painter, but not surprisingly they were not able to do so. There were lots of painters around in London in Bankes’ day, who would undertake work such as this.

So far as we know there have been three different Haberdashers’ Halls. The first was the building that John Bankes knew. It was built just after the Fire of 1666 and destroyed in the World War 2 bombing. The next hall, familiar to us because we spent quite a bit of time researching there, is the building in Staining Lane that a number of us will be familiar with. This was demolished in the late 1990s, when the Company moved to their present location in Smithfield.

We visited the new Hall in 2008. It really is a lovely building. We were able to enjoy a leisurely walk around it, and reacquainted ourselves with the portrait of JB. Among the many interesting artefacts and paintings in the building a certain picture took our eyes. It is a specially commissioned view across the City of London and in the foreground the artist has included a number of prominent people in the company’s history. We were delighted to see John Bankes has been included in this, the artist having copied his visage from the portrait.

If any of you would like to visit the new hall I would suggest that the best way is probably to do as we did, and take advantage of the fact that the building is open to the public for one weekend in September each year, as part of the Open House London event.

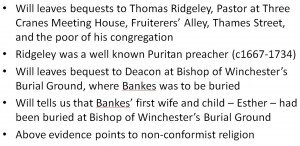

Evidence of John Bankes' religion

To fill in our picture of John Bankes it’s worth considering the nature of his religion. We live in a society in which a person’s religion is a matter for themselves, but in the late 17th and 18th centuries that was not the case. For instance, there were very severe penalties for being a Catholic.

Also, in a society where mortality rates were infinitely higher than they are nowadays, religion, and the question of what happens to one’s soul after death, was extremely important to people.

In Bankes’ will he left bequests to Thomas Ridgeley, the Pastor at Three Cranes Meeting House, which was near Paul’s Wharf, and to the poor of his congregation. It seems safe to assume that Bankes was a member of this congregation. Ridgeley was a well known Puritan preacher (c1667-1734).

Our man also left a bequest to the Deacon at the Bishop of Winchester’s Burial Ground, where he was to be buried. Indeed, the will tells us that Bankes’ first wife and a child named Esther had already been buried at Bishop of Winchester’s Burial Ground, which as I mentioned earlier was a non-conformist burial ground.

Although there were also bequests to the established church parish of St Benet Paul’s Wharf, this evidence definitely points to Bankes being a non-conformist as far as his religion was concerned.

11. John Bankes’ Residential Properties

We don’t have much information about John Bankes’ residential properties, but his business papers do contain some interesting references:

- Paul’s Wharf, London – this was his residence 1716 when he made his will.

- The Lottery, Nine Elms – Bankes’ home at Nine Elms is mentioned in his will. We know that Bankes had property in Nine Elms in the 1690s, and that his wife lived there after his death. We believe this house was called the Lottery, as it was referred to as such in a Court of Chancery document.

- The Mint, London – this house was mentioned in Bankes’ papers in 1697.

- Great house at Goodman’s Fields, Bethnal Green. This property features in accounts dated 1697 & 1698.

Now to When, but also with a bit of Where?

12. John Bankes’ Unresolved Query 1 – Birth

As you will have gathered from this talk, in spite of all the knowledge we have about John Bankes, there are mysteries that we have not come near to solving. Here are the two most important:

Firstly, his birth. When was he born (and where?)

As I mentioned at the start of this talk, the only evidence we have is inferred from other sources. We have not traced a baptism or birth, and sadly I suspect we never will, because his estimated birth date 1650-52 means that he was born during the Interregnum. Alas, there are few records for this period, when few parish registers were kept and still fewer survived.

Thus, Bankes’ birth date and birthplace is unknown, and his parentage remains a mystery.

Many years ago, when I was delving into the records at the old Haberdashers’ Hall, I found a rough note that said that John’s father was named Ralph Bankes. I’ve never come close to proving or disproving this, however, and I have no idea where the information came from. The Company Archivist at the time did not know the source of this assertion.

As mentioned earlier, we know, that John served his apprenticeship as a carpenter outside London, but have no idea when and where. The records of the Carpenters’ Company don’t help us, neither does the National Index of Apprenticeships.

13. John Bankes’ Unresolved Query 2 – First Marriage

As mentioned earlier, we have no idea when or where Bankes’ first marriage took place.

We know, from legal documentation recording land transfers, that the Atherton family had links with Marsh Baldon, Oxfordshire, but no marriage was found there, either by me or by Jane Stacey. The next slide shows you the relevant section of this document.

As I mentioned earlier, we have a note of a 1692 Poll Tax assessment that records Bankes, his wife and a child. It seems likely that he was married between about 1673 and 1692, probably in London, but that is quite a big time frame!

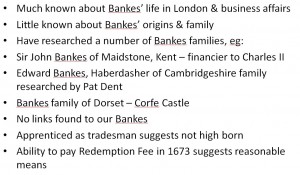

14. John Bankes Summing Up – An Enigma

So, in many ways John Bankes is an enigma to us.

John Bankes, Citizen & Haberdasher of London - An Enigma!

We know so much about his business affairs and his life in his London livery company, but so little about his origins and his family.

Either us or our fellow researchers have, over the years, researched a number of Bankes families, eg:

- Sir John Bankes of Maidstone, Kent – financier to Charles II

- Edward Bankes, Haberdasher of Cambridgeshire family researched by Pat Dent

- Bankes family of Dorset – Corfe Castle

In no case were any links found to our John Bankes.

The fact that he was apprenticed as tradesman suggests that he was not high born, but the fact that he was able to pay a substantial Redemption Fee in 1673 suggests he had access to reasonable means at a young age.

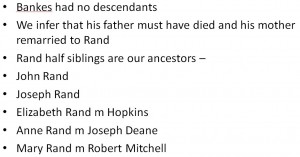

The Rands - Our Forebears

Lastly, In spite of all I’ve said about John Bankes, he was not actually an ancestor of any of us who are here today. He may have had siblings, and there may have been descendants of his siblings, but he had no descendants and we are all descended from his half brothers and sisters. Presumably his father must have died and his mother remarried to a certain Mr Rand, and that union produced several children:

- John Rand

- Joseph Rand, who we believe married m Deborah Swindall.

- Elizabeth Rand, who married Mr Hopkins

- Anne Rand, who married Joseph Deane, a carpenter

- Mary Rand who married Robert Mitchell, a feltmaker – my ancestor

We have some information about most of these people, but have never succeeded in tracing their lines further back in time.

Maybe that’s a job for my descendants!

Time to sign off!

- This page was last updated on Monday December 12th, 2011.