Mary Ann Archer & John Brown Smith

You can see references for the material displayed on this page by clicking here.

Index and Links to Sections.

- Mary Ann Archer and her Early Years

- John Brown Smith

- James Bayly Smith

- Excise Officer

- James Bayly Smith Leaves the Excise

- James Bayly Smith Death

- John Brown Smith, the Excise, his marriage and his family

- John Brown Smith leaves the Excise

- John Brown Smith and family post 1860

- Demise of John Brown Smith

- Mary Ann Archer post 1874

Mary Ann Archer and her early years

Mary Ann Archer was the only known child of Nathan Archer and Mary Ann Stephens. She was born on Friday 17 September 1830, and baptised at St John Baptist, Hoxton on Wednesday 13 October 1830[1]. She features on the Mary Ann Stephens & Nathan Archer page of this website.

St John the Baptist Church, Hoxton. Photographer: Fin Fahey

We know nothing of Mary’s early life, but our working assumption is that she probably lived in the household of her parents through her childhood years. We know that at Christmas 1839 Nathan Archer was living in a property at 15 Old Street Road [2], and this was where the family was enumerated when the 1841 census was taken on Sunday 6 June [3]. Mary Ann was recorded living with her parents and an apprentice printer. Old Street is one of the main roads running East – West to the North of the City of London, and for many centuries has been a busy main road.

Four years later, in March 1845, the recorded address of Mary Ann’s father was Wellington Place, Bethnal Green [4], which was a turning off the north side of Old Bethnal Green road, opposite Pollard Street. This road ran northwest to join up with Warner Place.

The death of Mary Ann’s father on 10 March 1845 [5], when she was only fifteen years old, must have been a severe blow to such a young lady. Our next sighting of her in the records occurred six years later, on Sunday 30 March 1851, when she and her 57 year old mother were enumerated at 1 Trafalgar Road, Shoreditch [6]. Trafalgar road ran north – south, parallel with Kingsland Road, and to the east of that main thoroughfare. Mary Ann Archer was 21 years of age, and working as a Milliner and Dress Maker. We do not know how she learned her trade. Typically, a milliner would serve two years apprenticeship, but as yet we have not found a record of an apprenticeship or a business or apprenticeship grant from the John Bankes Trust. We also do not know whether she worked from home or in an establishment such as a drapers’ shop, or whether she may have been an outworker for a millinery business. As no occupation was recorded against her mother’s name it would seem that young Mary Ann’s income was probably very important to the family.

On Monday 7 June 1852, at the age of 22, Mary Ann Archer married John Brown Smith, an Excise Officer. The ceremony took place at the church of St Mary, Haggerston, after the calling of banns, and both bride and groom signed the record of the event [7]. The address of both bride and groom was recorded as Nelson Terrace, which was a turning north off the City Road, a short distance east of The Eagle public house. The fact that the couple were recorded as sharing the same address does not necessarily mean that they were living together, although, of course, that may have been the case. Research into the extent of pre-marital cohabitation in the nineteenth century has found that only a very small number of couples lived together before marriage, but most genealogists will have come across marriage certificates that show the same address for both bride and groom. How to explain this? Rebecca Probert suggests that it is possible that there may have been a financial advantage to be gained by a couple by feigning cohabitation. This was because ‘the Victorian authorities were so concerned that couples may be living together before marriage that some clergymen and civil registrars offered to marry cohabiting couples for free’[8]

Back to top

John Brown Smith

So who was John Brown Smith? Where did he hail from? What did he do for a living? What do we know about his life?

Before considering these questions I think it appropriate to make a brief comment on the difficulty of investigating Smith family history, and the sources we have been able to use in this research. We shall also take a look at John’s parents.

My mother’s maiden name was Smith, and given the common nature of this name, tracing my maternal grandfather’s line backwards has always threatened to be fraught with difficulty. How do we identify our forebears amongst all the Smiths that appear in the records? However, because of the existence of the Bankes Pedigree Book [9] I and my fellow researchers were able to identify John Brown Smith as our ancestor. The existence of John’s middle name helped us in tracing several records relating to him, and when we discovered, through his marriage certificate, that his father was a certain James Bayly Smith, the existence of his middle name enabled us to trace several records about him.

Our research was further aided by the fact that, in the records we traced about James and John, the occupation of both of these men was recorded as Excise officers. The archives of the Excise department that are held by The National Archives at Kew, London, have enabled us to learn much about both of these men.

Holy Trinity Church, Minchinhampton. Photographer Adrian Pingstone

The result of these factors is that we have collected a considerable amount of information about these people, and I hope that visitors to this page will enjoy learning about them as much as we have.

John Brown Smith was baptised on 12 July 1829 [10], at Minchinhampton a small market town near Stroud in Gloucestershire. I do not know John’s date of birth but based on a variety of documents that we have used in our research we believe that it was shortly before his baptism.

Back to top

James Bayly Smith

On his baptism entry John’s parents were identified as James Bayly Smith, Excise Officer, and Alice. John was one of nine children known to have been born to James and Alice between c1828 and c1844:

| Date of Birth | Name | Location |

| abt 1828 | Michael Bayly Smith | Wolvercote, Oxon [11] |

| abt 1829 | John Brown Smith | Minchinhampton, Glos[12] |

| abt 1830 | Alice Isabella Smith | Minchinhampton, Glos[13] |

| Abt 1832 | George Smith | Prob Gloucestershire [14] |

| abt 1834 | Elizabeth Smith | Prob Gloucestershire [15] |

| Abt 1836 | James Smith | Prob Gloucestershire[16] |

| 21 Mar 1839 | Henry Graham Smith | Banwell, Somerset[17] |

| 22 Feb 1841 | Isabelle Emily Robertson Smith | Banwell, Somerset[18] |

| abt 1844 | Ann Smith | Somerset [19] |

James had married Alice Brown at Edinburgh on Christmas Day in 1825 [20]. We do not know why the marriage took place in Edinburgh. Maybe Alice had Scottish blood. Another possibility is that the couple were working in Edinburgh at the time, and decided to get married there. They were both said to be resident in St George’s parish, Edinburgh.

I know that James’s bride hailed from Northumberland because on the marriage entry she was said to be the daughter of Captain James Brown, of North Shields. Additionally, the evidence provided by the 1851 census shows that she was born c1801 in Northumberland [21].

A surprising piece of information gleaned from this marriage record is the groom’soccupation, which was stated as ‘Butler’. As I shall outline below, an official source, which I believe to be pretty reliable, shows that James was a clerk in his early working life. If he was working as a Butler in 1825 I assume that he had been trained in this role, and that he later worked as a clerk.

John Brown Smith and his siblings must have led a nomadic existence. Like his son some years later, James was an Excise Officer, and was moved around the country a lot. It was the policy of the Excise not to allow their officers to stay in one place for too long. Apart from any other possible considerations, this was done in order to prevent the officer from developing close relations with the people whose activities they were monitoring and thus making them susceptible to corruption. A look at the record of James’s postings evidences the application of this policy [22].

|

Date |

Posting |

Location |

| 3 March 1827 | Entered Excise Service | Battersea, London |

| 2 June 1828 | Filled vacancy as Officer | Sodbury, Glos |

| Abt 1829 [Date not stated] | Appointed Officer | Hampton, Glos |

| 20th December 1830 | Appointed Officer | Stroud, Glos |

| 16 April 1835 | Exchanged positions with John Mathias. Appointed Officer | Cheltenham, Glos |

| 20 August 1838 | Appointed Officer | Dunster, Somerset |

| 7 February 1839 | Appointed Officer | Wrington, Bristol |

| 21 May 1844 | Exchanged positions with John Harrison, Bristol 3rd Ride | Bristol |

| 2 January 1847 | On death of the Officer of Liverpool 8th Div., promoted to replace him | Liverpool |

At the time of the birth of John Brown Smith, James was serving at Hampton Ride, Gloucestershire, having been posted previously in London and Gloucestershire. By c1844, when the last of his known children was born, he had served at three other locations. At least these three places were all in two neighbouring counties; a longer distance move was forced on the family when James was moved to Liverpool, but at least that seems to have been a promotion.

One can imagine that these moves may well have had an adverse effect on the lives of

Signature of James Bayly Smith

members of James’s household. In his history of the Excise, Smith [23] (no relation!) acknowledges that families of excise men suffered ‘personal disturbance’ through such moves. Families were often living away from the locality of their relations, and their opportunity to ‘put down roots’ in a given locality was almost non-existent. Additionally, the sheer upheaval of moving about the countryside, given the state of transport in the period being considered, must have made moving personal effects a difficult matter. Smith also points out that excise men were often exploited by being forced to pay higher rents for their new accommodation when they moved.

Back to top

Excise Officer

It is worth considering, briefly, what life was like for an excise officer in the time of James Bayly Smith and his son. There appears to have been no shortage of applicants for vacancies in the service [24], and that fact may be regarded as proof that the terms and conditions of employment attached to the job were considered attractive. In fact, around 1800 the authorities introduced a rule that applications for posts in the Excise service would be accepted only from relatives of people currently in the service. This was done in order to reduce that size of the waiting lists.

Smith states [25] that Excise Officers were well paid in comparison to other employees in the nineteenth century, but this comment was based on the situation around 1800. I believe the value of the salaries of Excise Officers must have fallen in real terms over the next fifty years, as in March 1858 a general rise in salaries of ten per cent was awarded to them. Although this increase seems quite substantial, Smith [26] comments that it was small in relation to increases awarded to other workers at the time. It is, perhaps, also relevant to consider the very high rates of inflation that occurred in England in the period after the Napoleonic wars.

During the period 1782-1867 excise officers were not allowed to vote in elections because they would have made up approximately 20% of the electorate, and as such they were judged likely to have undue influence on election results [27]. It seems to me likely that the property qualifications for voting that existed in that period would have precluded many of them from voting anyway, so to a certain extent their exclusion would have been meaningless. Nevertheless, the exclusion did exist.

In the nineteenth century Excise staff was one of the few groups of workers who were in receipt of pensions, and as such they enjoyed something of an enhanced status compared to other working people. Another benefit they received was compensation for injuries incurred whilst going about their duties. There were payments stipulated in cases of loss of limbs, and in the event of a fatality, the excise man’s widow received monetary compensation [28]. The payment of such compensation bears testimony to the dangerous nature of the work of Excise men, who had to deal with some very unsavoury characters, such as smugglers, in pursuing their duties.

People wishing to join the excise service had to demonstrate that they were literate and numerate. These skills were obviously essential if the officer was to complete all the records that were expected of him, and carry out gauging. Applicants had to be trained in gauging by a local Excise Officer, and provide suitable references from a ‘person of substance’ [29].

We are fortunate that the annals of the Excise Department are very comprehensive. They include records relating to the procedures carried out when both James Bayley Smith [30] and John Brown Smith [31] entered the service, and provide us with an incredible insight into these people.

James Bayley Smith entered the service in 1827. The papers relevant to his appointment include a statement, written by him in January of that year, to the effect that he had not paid anybody in any way to influence the success of his application to become an Excise officer. This statement was supported by an affidavit from a certain Benjamin Payne, Supervisor at Battersea, which read as follows:-

May it Please your Honours

‘I have examined the above mentioned James Bayly Smith and find him well qualified in every respect …….. he understands the first four Rules of Vulgar and Decimal Arithmatic [sic]; he hath taken the Oath of Office and that of allegiance, and the said certificate and the above oath are of his own hand writing.’[32]

Whenever I get the opportunity, I enjoy the attempt to learn something of my ancestors from their handwriting. In this case I have a splendid example of James’s very best writing, and it certainly reveals him as a person of some style and education. [sig image ?]

A further reference, given by the same Benjamin Payne, stated that James was free from debt and that although he was married, he had no children. It was important to the Excise authorities that their officers were not prevented by their family circumstances from moving, hence the defensive tone of this statement. Indeed, in 1852 a regulation stated that recruits to the Excise after that date would be forced to resign their posts if they married before becoming Ride Officers [33].

The reference also stated that James was ‘well affected to the present Government’ and that he had previously been a Clerk.

James must have kept Benjamin Payne well occupied over the weeks following the above statements, as the same papers show that on 3 March 1827 he signed a statement certifying that

‘… James Bayly Smith, born at Colchester in the County of Essex Collection, aged 25 years is instructed ….. and is qualified for Surveying Common Brewers, Victuallers, Rectifiers of Acid, Distillers, Maltsters, Chandlers … Tanners, Brandy, Wine, Tea and Tobacco Dealers.

He can cast Excise and Malt Gages both by Pen and Rule, has taken Gages and Stocked for six weeks in Battersea 1st Division, and duly entered his Surveys in books prepared by him for that purpose, from which he has made true Vouchers and Abstracts ……and is in every respect well qualified for the Employment of an Officer of the Excise …’

What riches this source contained! In a single document I learned of James’s age and birthplace, and the training he had undergone.

It seems that James passed the stringent entry criteria of the Excise comfortably, and set out on his career in the service. I have already listed the bare facts about movements around the country. I will now attempt to demonstrate a flavour of the everyday service life of an excise officer in the nineteenth century.

I am fortunate that a book was written in the mid nineteenth century by a man who had been an Excise Officer for many years. The Recollections of a Gauger was written by Joseph Pacy, who joined the service in the same year as James Bayly Smith and eventually became a Collector. The book is a personal account of the everyday life of an Excise Officer, and if anybody reading this is interested enough to want to know more on this subject, I thoroughly recommend it [34].

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Payne’s account is his description of the typical working day of an excise officer, citing the example of the man who trained him. He relates how the officer rose early each morning, to unlock the equipment used by chandlers. Candles were taxed in the 1820s, and the chandlers’ equipment had to be locked up at night by the officer, and unlocked the next morning. After eating a hurried breakfast the officer called on innkeepers, to ascertain which of them were brewing. He would re-visit the chandlers every four hours while they were working, and also monitor the activities of tanners. After dinner he would weigh and measure the stocks of tea,

tobacco and spirits held by local traders, and after tea he had to do his record keeping. After all this, he completed his day with another visit to the chandler, to lock up his candle-making equipment [35].

Payne relates how excise officers worked a seven-day week:

‘Jaded and tired, he would retire to rest, only to rise in the morning to pursue the same round of duties.’[36]

The long hours were not the only problem of the Excise Officer. His business was the levying of taxes, so by the nature of things he was not a popular visitor to the people under his supervision. It is, therefore, not surprising to learn that sometimes chandlers, maltsters and the like were less than co-operative. Payne tells how, in the early years of his service, a chandler suggested that he should leave the keys to his equipment with him, so that he could save the officer the trouble of visiting him at morning and night. Payne refused to do this, knowing that discovery of such an act would lead to his dismissal. However, the chandler responded by signalling his non-co-operation. He made Payne unlock his equipment at the unearthly hour of 1am [37].

Back to top

James Bayly Smith Leaves the Excise

On 23 November 1847 a notice appeared in The London Gazette [38] that concerned James Bayly Smith. It announced that James had become an Insolvent Debtor, his case being administered by Liverpool District County Court, where he had been granted an interim order giving him protection from the demands of his creditors. He was said to be living at 1-6 Field Street, Everton, and was summoned to appear in court on 29 November 1847 at 10 am, to be examined about his debts, estate and effects. His debtors, and anybody holding any of his effects, were instructed not to pay him, but to contact the Official Assignee who was dealing with the case.

In earlier times James Bayly Smith may well have ended up in prison; many people had been incarcerated for debt over the centuries, including such illustrious people as Emma Hamilton and John Donne. However, he was fortunate that the Act for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors of 1842 was in force at the time of his insolvency. Under this legislation any trader who owed his or her creditors less than £300, or any person who was not a trader, could apply to the court for a protection order that would prevent any debt recovery proceedings being taken against him or her. In return for this protection the insolvent person would have to pass all their property over to an Official Assignee. It seems from the London Gazette notice that James had made such an application, and that an interim protection order had been granted in his favour, pending the result of the court’s investigation of his affairs. Hopefully, he may not have gone to prison.

If we recall that on joining the service excise men were examined to prove that they were not in debt, and the lengths the Excise went to in endeavouring to make sure that their excise men were not beholden to anybody, we can see why an officer who became an insolvent debtor would forfeit his career in the service. Thus it was that James Bayley Smith’s career as an Excise Officer ended, although it appears that a year passed before he was subjected to disciplinary procedures by the Excise. The relevant record reads:

‘Wednesday 15th Novr 1848

Whereas James Bayly Smith, Officer of Liverpool 8th Division, Liverpool Collection, who by a minute of the 13th instant was placed on the List of dropt Officers, became while Officer of Bristol 3rd Ride, Bristol Collection, indebted to a Tea and Tobacco Dealer in that Ride, and it further appearing that he is not free from debt, Ordered that he be discharged.’[39]

Some weeks later James petitioned the Board, asking to be reinstated. This was refused. However, the records show that on 15 March 1849 his discharge was converted into a ‘relinquishment’[40], which I interpret this as meaning that he was allowed to resign, rather than being sacked.

Pacy concluded his Reminiscences by commenting on the financial circumstances of excise officers. He said that whereas in the past officers had received a percentage of the value of the fines and seizures resulting from their work, in his time their only payment was their salary. They were, he said, expected to:

‘… live respectably, dress genteelly, and keep up a good appearance, on an income barely sufficient to keep the wolf from the door.’[41]

I paraphrase his view by citing the modern saying – ‘If you pay peanuts you get monkeys’. He urged the authorities to improve the lot of these men.

It is not my role to excuse the deviant acts of my ancestor, but from what I know about James Bayly Smith, he does not seem to have been a stupid man. It seems possible that the breach of regulations that caused his dismissal from the Excise Department may have been due to the fact that he simply could not manage on his salary. Of course, it is possible that he was feckless or corrupt, but I prefer to give him that benefit of the doubt.

Back to top

James Bayly Smith Death

James’s story concluded with his death in Liverpool, less than sixteen months after he lost his post as an Excise Officer. We do not know whether his health deteriorated as a result of his dismissal from his job, but this may have been the case. He died at an address in Castle Street, Everton on Friday 5 July 1850. Castle Street runs north – south in the docks area of Liverpool, and In modern times passes over the Queensway Tunnel. The cause of James’s death was recorded as ‘Serious Apoplexy 21 Hours’[42]. His death was registered the day after the event by his son – John Brown Smith, who evidently tried to present his father in the best possible light by stating his occupation as ‘Officer in Excise’.

Back to top

John Brown Smith, the Excise, his marriage and his family

When John Brown Smith appeared on the census that was taken on Sunday 30 March 1851 he was living with his mother and three of his siblings at Rose Vale, Everton [43]. They had moved a short distance eastwards from Castle Street, and near to Field Street, where, as we have seen, James, and presumably the family, had lived in November 1847. On this census John was said to be following the occupation of a Wine Cooper. We do not know where he learned this trade; maybe he served an apprenticeship, but we have never seen any evidence of that.

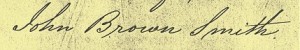

Signature of John Brown Smith

One would have thought that his father’s dismissal from the service may have made it less likely that John would be admitted as an excise officer, but that does not seem to have been the case. It also seems that the long hours worked by his father, and the fact of his dismissal, did not deter John from seeking a career in the Excise.

The records of John Brown Smith’s entry into the Excise service [44] are broadly similar to those described above in connection with his father. He was certified to be numerate and literate, and there is a declaration, in his own hand, stating that he had not paid anybody to influence his application for employment as an excise officer.

In John’s case we also have a copy of the arithmetical calculations he worked to demonstrate to his examiners that he was proficient in arithmetic. His application was dealt with in Liverpool in the Spring of 1851. He was appointed to his first post in the Excise department on 14 June 1851 in Liverpool, but within two months he was moved to East London. It seems unlikely that John and Mary Ann Archer could have met before John moved to take up his post in London, so we deduce that their courtship lasted about ten months at most.

John Brown Smith probably seemed a reasonably good ‘catch’ for the young Mary Ann. Although I do not imagine that he was particularly well off materially, his status as an Excise Officer and evident good education would probably likely have marked him out as a respected figure in his community.

Within a year of their marriage, John and Mary Ann Smith were forced, by the demands of John’s employer, to move to a new location, and for the next seven years their residential record outlines something of an odyssey. Starting with their first child – my great grandfather – the five known children of Mary Ann and her spouse were born at the following dates and places:-

| Date | Name | Location |

| 3 May 1853 [45] | James William Smith | Newcastle Under Lyme, Staffs |

| 8 March 1855[46] | John Henry Smith | Watlington, Oxon |

| 10 September 1856[47] | Jessie Alice Smith | Watlington, Oxon |

| 14 November 1858[48] | George William Smith | Lambourne, Berkshire |

| 17 August 1863 [49] | Michael Archer Smith | Shoreditch |

St Mary & St Giles Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire. Photograph: Martin Baird

The first three children born to Mary Ann (Archer) Smith and her spouse were all baptised together at St Mary & St Giles,Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire on Saturday 19 May 1858. Stony Stratford was then a small town, which was widely known in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century as a stopping point for coaches travelling from London to the north of England. In the record of the Smith baptisms the home parish of the family was stated as ‘St Mary Magdalen’ [50].

After his marriage John Brown Smith’s employment record with the Excise shows that the life of his household was every bit as nomadic as that of his father. His recorded movements were as follows [51]:

|

Date |

Posting |

Location |

| 26 October 1852 | Appointed Expectant. | Surrey |

| 7 January 1853 | Appointed Expectant. | Stafford |

| 21 April 1853 | Appointed 2nd Assistant | London East |

| 17 October 1853 | Dropped …. (to) be provided for on the first convenient vacancies | |

| 19 May 1854 | Appointed Supernumerary | Reading |

| 22 July 1854 | Appointed Officer | Watlington Ride, Reading |

| 15 April 1857 | Appointed Officer (at own request) | Stratford 1st Ride,Northampton |

| 23r July 1858 | Transferred, having incurred the displeasure of the board | Lambourn Ride, Oxford |

| 24 August 1860 | Appointed Officer | Wantage Ride, Reading |

Compared to his father, John’s service in the Excise department took him to more different places in the Midlands and Home Counties, which made searching for the birth records of his children quite difficult. Normally such a search for people with a name as common as Smith would probably be unsuccessful. However, as I mentioned above, I and my fellow researchers had obtained the names of the children from the Bankes Pedigree Book, and as we knew the locations at which John served, between us we were able to track down these events.

Back to top

John Brown Smith leaves the Excise

From the above list of the locations at which John Brown Smith served the Excise Department readers will note that in July 1858 he ‘incurred the displeasure of the board’. One may have hoped that John would have learned, from his father’s experience, the consequences of breaching the conditions of his service, but apparently that was not so. After 1860 the rest of his Excise career was recorded as follows [52]:

| Date | Detail |

| 29 November 1860. | Suspended |

| 20 December 1860 | Suspended & Dismissed “following feigned survey at maltsters and other neglects and irregularities. |

| 12 April 1862 | Petitioned the Board for restoration. Rejected. |

An entry in the records of the Excise dated 20 December 1860 reads (53):

‘Whereas John Brown Smith, Officer of Wantage Ride, Reading Collection, who by minute of the 29th ultimo, was ordered to be suspended showed surveys at Maltsters for November 17th, 19th, 20th, 22nd, 23rd and 24th without making corresponding entries on the specimens kept on their premises, thereby indicating such survey to have been feigned: Whereas he borrowed money from a Maltster under his survey: Whereas he has been guilty of numerous other neglects and irregularities and the Revenue is not safe under his care: Whereas he left the letting on the 26th Ultimo without leave and absconded: and whereas he has been reprimanded and once admonished within two years last past and removal on complaint, Ordered that he be discharged.’

The list of John’s misdeeds was long, and it is difficult to imagine that he could have had any hope of escaping dismissal. Without wishing to seem too censorious, it is apparent that he had erred previously, and been given a chance to improve his conduct. However, he seems to have been incapable of changing his ways.

Back to top

John Brown Smith & family post 1860

The available evidence suggests that soon after losing his position in the Excise John and Mary Ann Smith moved their family to live in London. This appears to have been a logical step, since Mary Ann was a Londoner by birth and upbringing, and a move to the capital would bring her closer to her kinsfolk. Not only that, but London would offer more employment opportunities for John. The census that was held on Sunday 7 April 1861 enumerated the couple and their young family as follows[54]:

| Name | Rel to Head | Marital Status | Sex | Age | Occupation | Birthplace |

| John Brown Smith | Head | Mar | M | 32 | Wine Cooper | Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire |

| Mary Ann Smith | Wife | Mar | F | 30 | St Luke, Middlesex | |

| John Wm Smith [sic] | Son | M | 7 | Newcastle, Stafford | ||

| James Hy Smith [sic] | Son | M | 4 | Watlington, Oxon | ||

| George Smith | Son | M | 2 | Lambourn, Berkshire |

Apart from the fact that the enumerator evidently mixed up the names of James William Smith and John Henry Smith in this entry, there are a couple of other points of interest. Firstly, an annotation against the entry for John Henry Smith stated that he had been ‘part blind from birth’. Secondly, we see that John Brown Smith had taken up employment as a Wine Cooper, reverting to the trade he used to work in prior to joining the Excise (see the 1851 census entry referred to above). We do not know whether he was in business on his own account, or an employee.

By May 1864 John was no longer working as a wine cooper, being employed as a Railway Clerk. He was living 21 Brandon Street Clapham [55], and to judge from the fact that Mary Ann was enumerated in the household on both the 1861 and 1871 censuses, it seems likely that she was also resident at that address.

At this time a great tragedy had struck the family. Nine months earlier a fifth child had been born to Mary Ann & John Brown Smith – a son named Michael Archer Smith, but this child had lately fallen ill with infantile fever, and on Friday 6 May 1864 he died at the family home [56]. We do not know what caused the fever.

We next find our Smith family in the records of the 1871 census, which was taken on 2 April of that year [57]:

| Name | Rel to Head | Marital Status | Sex | Age | Occupation | Birthplace |

| John Brown Smith | Head | Mar | M | 42 | Clerk | Minchinhampton, Gloucestershire |

| Mary Ann Smith | Wife | Mar | F | 40 | Shoreditch, Middlesex | |

| James William Smith | Son | M | 17 | Engineer | Newcastle | |

| John Henry Smith | Son | M | 16 | Builder | Watlington, OxfordshireNote: Imperfect sight from birth | |

| George Smith | Son | M | 13 | Lambourne, Berkshire |

The family had now moved back to North London, and were enumerated at 4 Baches Row, Hoxton, an address that lay off Charles Square, a short distance from the modern Old Street underground station. Once again, the enumeration contained a reference to John Henry’s imperfect sight. We note that John Brown Smith’s occupation was shown as “Clerk”, it seems likely that this was an abbreviation of “Railway Clerk”.

Whilst the 1871 enumerator managed to list the family names accurately, he failed to add “Staffordshire” when recording James William’s birthplace as Newcastle, making this aspect of the record prone to misinterpretation.

We can see from this entry that John Brown & Mary Ann Smith’s daughter, Jessie Alice, was not in the household on the night of the enumeration. Instead she can be found at 32 Broke Road, Haggerston, Shoreditch [58] with her maternal grandmother, Mary Ann (Stephens) Archer. We have no way of knowing whether she may have been on a short visit, or whether she was living with her grandmother permanently at that time. Jessie was 14 years of age at the time, and no occupation was recorded against her name.

On Sunday 2nd August 1874 at the church of StThomas, Bethnal Green, in East London, John Brown Smith attended the wedding of his and Mary Ann Archer’s second son – John Henry Smith. The bride was Mary Rebecca Mills, daughter of Henry Mills, an engineer, and his wife Matilda (nee Nunn). John Brown Smith signed as a witness to this event [59]and his daughter, Jessie Alice Smith, signed as the second witness. It seems probable that Mary Ann (Archer) Smith was also in attendance. According to this record John was still employed as a Railway Clerk.

Back to top

Demise of John Brown Smith

The final episode in John Brown Smith’s life occurred in sad circumstances. On Saturday 24 October 1874 – within three months of John Henry Smith’s marriage – he was admitted to Fisherton Anger Lunatic Asylum, at Salisbury, Wiltshire. The asylum’s records show that he was aged 46, married, and employed as a ticket collector – presumably on the railway. His address was stated as 72 Westmoreland Place, City Road, London, and he had been sent to the asylum under the authority of the Police Magistrate. His mental disorder was stated as ‘Mania’, caused by ‘Overwork’, and his condition was ‘Feeble’ [60].

Westmoreland Place lay to the North of City Road, and was very near to the Eagle public house, which features in the rhyme ‘Pop Goes the Weasel’. It was situated to the south of Wenlock Street, the stated place of residence of John Henry Smith when he married.

Why, I hear you ask, was John Brown Smith sent to an asylum in Wiltshire? Surely, there must have been an asylum that could have dealt with his case in London? I found the answer in an 1874 local newspaper [61]. An item described how the local Relieving Officers had reported that all the asylums in the county were full and the nearest asylum that had vacancies was Salisbury. The alternative to sending people there was to put ‘lunatics’ in the workhouse, but the legal position was that such persons could only be kept in the workhouse for ten days. The Shoreditch Board of Guardians reportedly stated that they believed it ‘…absurd, extraordinary and cruel to send lunatics to Salisbury Asylum …’ However, the evidence of John Brown Smith’s case shows that that was what was done.

For the person under treatment, being sent from London to Salisbury must have been a traumatic experience. He was presumably isolated there, miles from home, with little likelihood of receiving visits from relations. For the relations, also, this must have been a traumatic experience. In an era that predated the telephone service, any news they received of their loved ones must have arrived by post. It would have been at once impersonal and late! This, I imagine, must have been the situation endured by John Brown Smith and Mary Ann (Archer).

We are fortunate that, through the help of Wiltshire Archives Service, we have been able to obtain a copy of the record of John Brown Smith’s treatment while he was in Fisherton Anger Asylum [62]. His physical description included the information that he had grey eyes and brown hair with a moustache. On his admission he was described as:

‘A male pauper patient, age 46 married … who was … not subject to epilepsy but is suicidal..…. He is restless and excited. He talks in a rambling manner; he imagines that he is rich; his memory is defective and he has difficulty in expressing himself when asked a question.’

On Monday November 9 1874 it was recorded that in addition to the above symptoms:

‘He frequently partially undresses himself.’

His physical condition seems to have remained constant until Thursday 7 January 1875, when it was recorded that:

‘This patient has grown much more helpless and weaker – ordered to bed.’

John’s condition then worsened progressively, until he died at 9.30am on Friday 29 January 1875. The cause of death was stated as Paresis, which I understand to mean partial paralysis. I have obtained a copy of John’s death certificate, but it does not add any information to that contained in the asylum records.

John Brown Smith was buried in a pauper’s grave at Fisherton Anger Burial Ground on Tuesday 2 February 1875 – a somewhat ignominious end for an obviously talented, if flawed, man. The record of his burial shows that he was interred in consecrated ground, in a grave to the north of the chapel [63]. I wonder whether his wife was present at his interment. My guess is probably not. The ceremony took place only four days after his death, and it may not have been possible for her to attend at short notice if she was living in London. As John was recorded as a pauper it seems unlikely that Mary Ann had much in the way of material assets. If she had been able to afford it, possibly she may have ensured that her husband received a more appropriate burial.

Back to top

Mary Ann Archer post 1874

We have tried to discover what became of Mary Ann (Archer) Smith after her spouse’s death, without much success to date. We have traced her on the census taken on Sunday 3 April 1881 [64], living at 71 Shrubland Road, Dalston, Hackney in the household of her elderly mother. Her daughter – Jessie, and son – George were present, as was Jessie’s two year old daughter – Mary A Smith. The fact that no occupation was recorded against Mary Ann’s name suggests that she was probably supported financially by her mother, who was described as an annuitant, and her two children, who both were working. She no doubt helped to care for her daughter’s child.

In 1881 Mary Ann was aged fifty years, and could still look forward to many more years of life, given good luck with her health. I do not know what became of her after this date. I have been told that she died in the early years of the twentieth century, but as yet we have not traced the record of her death. Unfortunately there are a large number of Mary Ann Smiths recorded in the civil register, and finding the correct one is no easy task! Hopefully, some day we may fill this gap in my family history.

Back to top

- This page was last updated on Sunday January 27th, 2013.